Bangladesh Breaking News

Exiled and Under Attack: Bangladesh’s Former Ruling Student Wing Faces Retribution and Bans Under New Regime

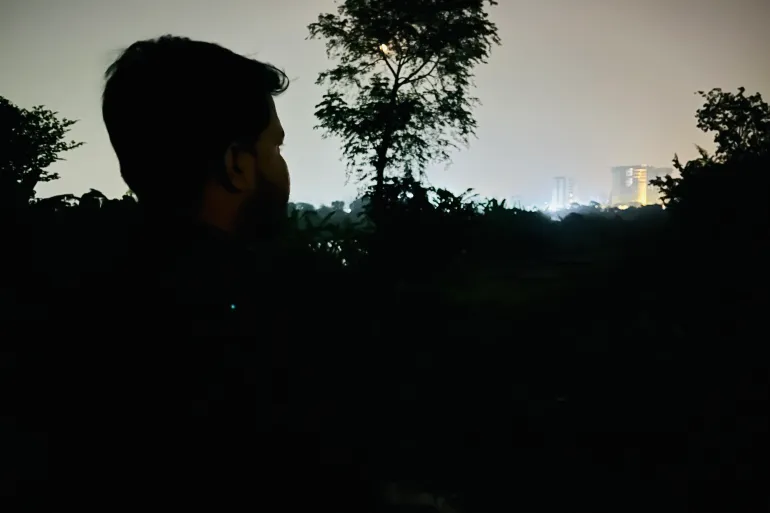

Dhaka, Bangladesh – Fahmi, a 24-year-old former student leader at Dhaka University, is now a fugitive. Once a dominant figure within Bangladesh Chhatra League (BCL) — the student wing of former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s Awami League (AL) party — Fahmi is one of thousands now hiding, facing threats of arrest, violence, and social exile in the wake of a political upheaval that ousted Hasina from power.

On Wednesday, Bangladesh’s interim government, led by Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus, declared BCL a “terrorist organization,” citing a history of “serious misconduct, including violence, harassment, and exploitation of public resources.” This ban marks the latest turn in a tumultuous chapter for BCL affiliates, many of whom face charges of alleged rights abuses during Hasina’s rule.

From Power to Persecution

“Not long ago, I was a voice of authority here,” said Fahmi, an applied chemistry undergraduate. “Now, I am running like a fugitive with no probable future.”

The experience of Fahmi mirrors that of countless others: former student powerbrokers who now live in fear. Despite his initial reluctance, Fahmi joined BCL to enhance his career prospects. With party connections, he felt, came security and job stability in a country with limited opportunities. “I wanted to serve the country,” he said. “But now, even stepping onto campus could lead to my arrest — or worse, I could be beaten to death.”

Reflecting on his involvement, he now regrets prioritizing party demands over family. After his father’s passing in 2022, Fahmi left his grieving family to attend a commemorative event for Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Sheikh Hasina’s father and a central figure in Bangladesh’s independence. “Looking back, I see I prioritized the party’s approval over supporting my family,” Fahmi said.

Path to Hasina’s Ouster

turning point for Hasina and her party’s student affiliates came in July. What began as protests over a contentious reservation system in government jobs soon morphed into widespread opposition to Hasina’s rule, which many labeled “autocratic.”

regime’s violent response — using live ammunition, tear gas, and mass detentions — resulted in over 1,000 deaths and thousands of arrests. On August 5, amid violent unrest, Hasina fled to India. Following her departure, a wave of retribution swept across the country, targeting former members of her government and BCL leaders.

“My family’s home and business were torched by anti-Hasina protesters,” said Fahmi. His younger brother was threatened and bullied at the madrasa he attended. Now, Fahmi and others like him live in hiding, fearing for our lives.

From Protest to Political Reform

Led by Yunus, the interim government moved swiftly to implement changes, including the BCL ban, formalized on October 23 under the Anti-Terrorism Act 2009.

Ban followed demonstrations organized by Students Against Discrimination (SAD) and or groups that had campaigned against Hasina’s government. Abdul Hannan Masud, a founding member of SAD, said, “Chhatra League cannot operate in Bangladesh. All our operatives will be identified and brought to justice.”

As police crackdown on BCL leaders, students like Fahmi, Shahreen Ariana, and Ors now live in fear of arrest on university campuses. family of Ariana, a BCL leader from Rajshahi University, claimed her October 18 arrest was based on “forged charges.” Local authorities, however, insist she had prior cases pending.

Legacy of BCL and a Nation in Transition

Despite official statements, the crackdown has drawn criticism from prominent voices. Khalid Mahmud Chowdhury, a former minister in Hasina’s cabinet, argued that isolating BCL members from higher education risks exacerbating social divides. “How can Dr. Yunus hope to build a better future for Bangladesh while excluding such a significant segment of its youth?” Chowdhury asked. He assured loyal BCL members that the party remains steadfast in its support, pledging to fight for their educational rights.

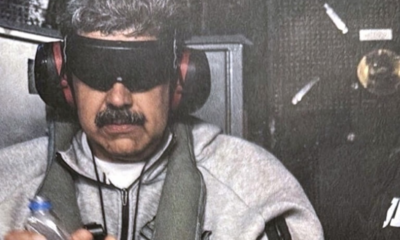

Meanwhile, Sujon, a senior BCL leader in hiding, shared his experience at a dimly lit cafe on the outskirts of Dhaka, far from any familiar faces. Now fearful for his life, Sujon expressed regret for his political alignment, remarking, “I grew up in a generation that only saw Awami League in power. Aligning with m was the only option.”

Thousands like Sujon and Fahmi are grappling with sudden instability as Bangladesh reshapes its political landscape, shifting from one-party dominance to an uncertain, potentially more democratic future. The question remains: What will happen to thousands of student activists who find themselves exiled within our nation?

- Bangladesh’s new outcasts: Students from ex-PM Hasina’s party now in hiding Al Jazeera English

- Bangladesh could ban Awami League The Economic Times

- Bangladesh’s Student Politics: Storied History, Brutal Violence The Diplomat